A carpenter doesn’t discuss with their client what chisel to use. Yet in data and AI, the tool tends to become the conversation.

A carpenter’s tools stay in the bag until the job is clear. It’s about measuring the room, talking about shelves that will hold, doors that will close, and a finish that will survive sticky hands and summer heat.

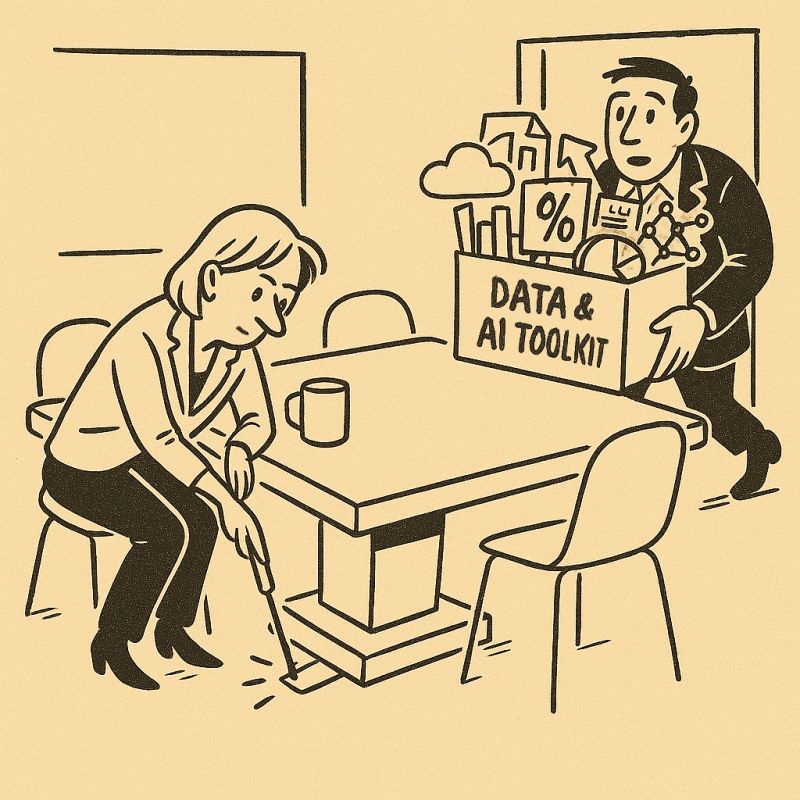

Not so in data and AI. We hold meetings that in essence are trade shows, invoke acronyms as if they were outcomes, and then wonder why the product feels the same and the numbers don’t move. But the physics of value are plain. Enterprises don’t need algorithms. They need faster answers, fewer errors, less friction, more trust.

If a datapoint doesn’t change a behaviour that matters, the data lake is a decorative (?) pond. The test is simple: when the system goes live, what will someone do differently, and what number will you show the CFO three months later? If you cannot answer both, you are polishing a chisel.

As a litmus test, explain the project using the verbs your users perform—search, buy, book, return, renew—and the nouns your finance team recognises—margin, conversion, churn, cash. Say what the person on the other side of the screen will experience and why that experience will change the number on the page. If that story is thin, your stack is a distraction.

Then follow the carpenter’s sequence: Begin with the job to be done. Specify the load, the tolerance, the edge cases, the deadline, the cost ceiling. Confront the constraints that will not move: regulation, latency, brand risk, skeletal staffing. Decide where a human must stay in the loop and where automation may reasonably stand alone.

Only then pick the smallest, plainest tool that clears the bar. Often that tool is not “AI” at all, or even data. A rule, a queue, a minor change to a workflow will often do more in a quarter than a grand build will do in a year. The heresy is that boring solutions compound.

None of this is an argument against good tools. At scale, choices about models, infrastructure, and pipelines deserve care. But they should be chosen for the job, not the job stretched to fit the tool.

There is a cultural shift available to any team that wants it: Start meetings with the problem, the user, the single number that defines success, the boundaries you will not cross, and the date you will decide to stop. Assign an owner with the power to say no and the duty to publish the result. Protect the engineers from tool theatre and give them a crisp spec. If they need a sharper chisel, they will say so.

Build the thing that holds and let the toolmarks vanish.