If we want value from data, it’s not enough to teach people how to read charts. We also need to teach them how to read themselves.

It’s a simple but counterintuitive fact: Understanding data doesn't automatically lead to better decisions. Think about it: How often have you seen someone presented with perfect data, clear insights, and compelling visualizations... only to make the same decisions they would have made without them?

A lack of Data Literacy can be part of the problem. But that’s just one piece of the puzzle. An even more common—and oftentimes overlooked—issue is misunderstanding how humans actually make decisions when presented with data. A lack of Decision Literacy.

The psychology of decision-making runs deeper than we think. Even with the most robust data governance, clear metrics, and advanced analytics capabilities, organizations will still fall prey to human tendencies, such as loss aversion, anchoring bias, and the sunk cost fallacy. These psychological factors don’t just interfere with our decisions once the data is there—they already shape how we collect, analyze, and interpret data in the first place.

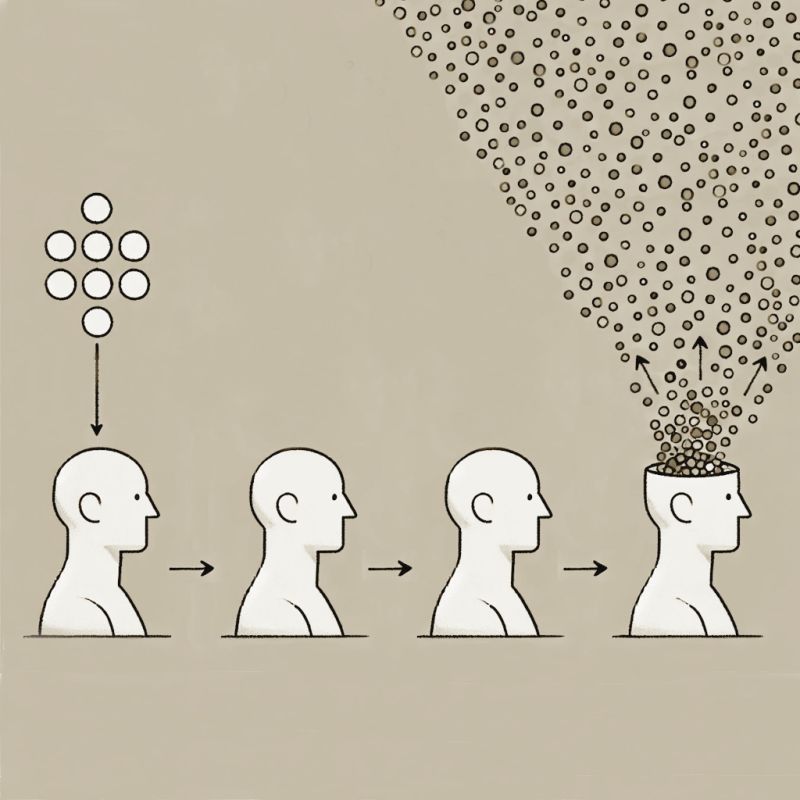

The more skilled we become with data, the more sophisticated our self-deception can become. Cognitive biases don’t disappear just because we know how to interpret bar charts and probabilities. On the contrary! The illusion of data mastery can make us even more vulnerable to confirmation bias. Our brains are excellent at finding data that supports our pre-existing beliefs while unconsciously filtering out contradictory evidence.

True data mastery requires us to be as fluent in psychology as we are in programming. We must therefore expand our common definition of data-driven transformation to account for this:

▪️ Beyond teaching people how to analyze data, we must help them understand decision-making.

▪️ In addition to building databases, we must also build decision-making frameworks that account for human nature.

▪️ When asking, “What does the data tell us?” we must also ask, “What might prevent us from seeing what the data tells us?”

The most successful organizations I've worked with understand that reading data and reading ourselves are equally critical skills for success. They create environments where it's safe to challenge assumptions, and decisions are reviewed not just for outcomes but for processes.

So ask yourself this: When was the last time your team discussed cognitive biases, group dynamics, and decision frameworks with the same rigor as your data stack?