Some data silos are organizational wisdom, not corporate sin.

In the world of data, "silo" has become the all-purpose insult. Executives rail against it, software vendors peddle “silo-busting” tools, and managers are convinced that if only they could tip every departmental datapoint into a unified structure, truth would reveal itself.

That dogma is tidy, uplifting—and wrong. Optimal data strategy isn’t universal integration; it’s pricing each boundary and cutting doorways only where the toll is worth paying.

It's easy to understand the allure of central pipes, single sources of truth, and glossy dashboards. The promise is appealing: once finance, marketing, and logistics numbers share a home, machine-learning models will serenade everyone with clarity and perfect forecasts.

This is a one-sided view, however. Boundaries exist for a simple economic reason—when the cost of crossing them is higher than the cost of keeping things inside. Data is no exception. So before we shout "tear down that silo," we should ask a simple question: What is the boundary costing us—and what is it saving us?

Not all data silos are moral failures; they can also be the organizational form that minimizes the sum of friction and confusion in a given setting. They allow domain experts to optimize for local meaning without diluting signals for a generic, lowest-common-denominator schema.

Overly aggressive integration can hurt just as much as no integration. Chase universal data too hard, and analysts will spend their entire day untangling duplicates, resolving definition collisions, and chasing edge cases.

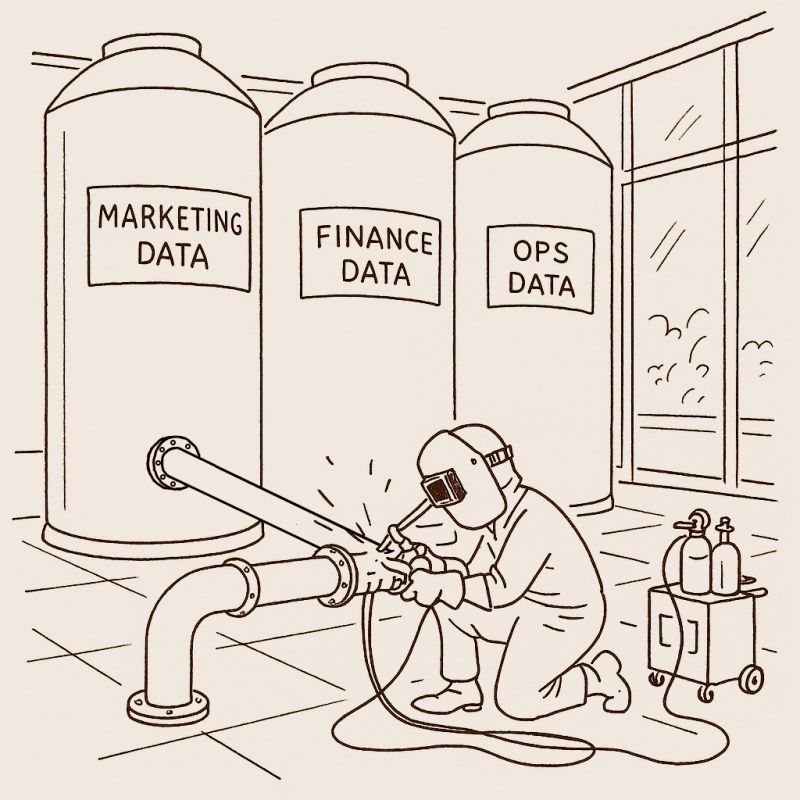

The real issue isn’t silos per se. It’s force-welding them together without pricing the welds. Federated approaches recognize this reality, advocating for domain ownership while establishing standards for interoperability. In a way, these approaches acknowledge that silos work—if, that is, they are consciously aligned with organizational needs and connected through well-designed interfaces and metadata.

Smashing every barrier is not bold leadership; it is the refusal to choose. The craft lies in deciding which boundaries to keep and where to carve doorways. Make those decisions explicit—priced, metered, and revisited—and your silos stop being bunkers, but become part of an interconnected, sprawling neighborhood.